Shaleka Dawit Woldegiorgis: Exiled Former Official Fueling Regional Unrest

A twilight provocateur peddles dangerous territorial claims from distant exile, twisting history to justify aggression against Eritrea's sovereignty. His warmongering rhetoric betrays his mercenary motives and dangerous disconnection from regional realities.

Amanuel Biedemaraim

Exposing A Twilight Provocateur's Dangerous Historical Revisionism: A Response to Shaleka Dawit's "Eritrea and Ethiopia: The Question of Access to the Sea"

Introduction:

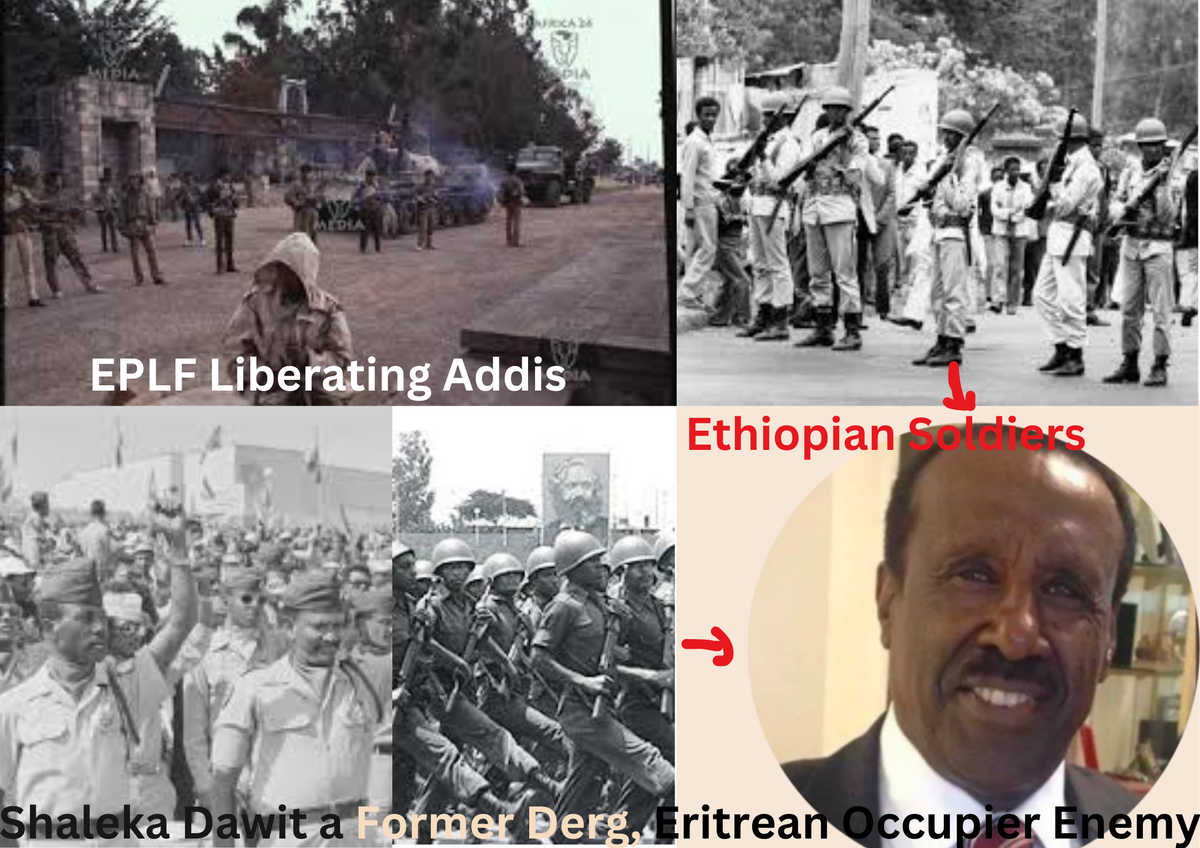

In an era where regional stability and peaceful coexistence are paramount, it is alarming to encounter warmongering rhetoric masked as historical analysis to justify aggression. A recent piece by Shaleka Dawit, an 80+-year-old former Ethiopian official who served under Emperor Haile Selassie and the Derg regime, presents a dangerous revisionist narrative about Eritrea's sovereignty and Ethiopia's supposed 'right' to its territory. His arguments not only distort historical facts but also advocate for territorial aggression under the guise of 'missed opportunities' - a particularly alarming stance from someone who witnessed firsthand the devastating human costs of regional conflicts.

This is not merely an academic disagreement about historical interpretation. When a former official with decades of government service deliberately misrepresents Eritrea's hard-won independence, dismisses its thirty-year liberation struggle, and suggests mechanisms for territorial acquisition in violation of international law, it crosses the line from historical analysis into dangerous provocation. Such rhetoric, especially from a known elder who served at the highest levels of Ethiopian government, risks poisoning the minds of future generations and undermining the foundations of regional stability.

Shaleka Dawit: “When Eritrea was granted its independence by the TPLF, Ethiopia lost something of enormous importance to its well-being: access to the sea."

AB: The end of Ethiopia's temporary access to Eritrean ports in 1991 came with Eritrea's hard-won independence, achieved through a 30-year liberation struggle led by the EPLF (Eritrean People's Liberation Front). This access had only been possible due to Ethiopia's illegal annexation of Eritrea in 1962, which violated the UN-mandated federation of 1952. Far from being 'granted' independence, Eritrean forces fought determinedly from 1961 onward, developing such military and organizational prowess that they not only secured their independence but also played a crucial role in the Ethiopian civil war's conclusion - including the EPLF's support in escorting TPLF forces into Addis Ababa in 1991. The EPLF had, in fact, served as a model and mentor for the TPLF in the mid-1970s when TPLF leaders received training in Eritrea.

Shaleka: “As a condition of its federation with Eritrea in 1950, Ethiopia could have demanded a formal partitioning of Eritrea, acquiring the port of Assab outright to guarantee a viable harbor. It did not make this demand.”

AB: The 1952 federation arrangement between Eritrea and Ethiopia was not a bilateral negotiation in which Ethiopia could make territorial demands. Rather, it was an internationally mediated process led by the United Nations, with significant involvement from Britain and the United States. Following Italy's defeat in 1941, Emperor Haile Selassie's position largely depended on Western powers. The federation decision was primarily shaped by international interests, particularly US strategic considerations, as evidenced by the 1953 US-Ethiopia agreement. The subsequent annexation of Eritrea in 1962 aligned with long-standing Ethiopian territorial ambitions, which had received implicit Western support.

Shaleka Dawit: “Under normal circumstances, a long-standing OAU declaration would have effectively barred Ethiopia from demanding Assab in 1991. That declaration states that countries will abide by the boundaries inherited from colonial times—which would be Eritrea’s boundary at the time of Italian occupation.[iii] But taking into consideration the UN’s role in the 1940s and its commitment to providing Ethiopia with access to the sea, Ethiopia could have established a legitimate argument for access in 1991 either through mediation or by taking the case to court.”

AB: The suggestion that Ethiopia could have made a "legitimate argument" for access to the sea in 1991 based on UN actions in the 1940s is historically and legally flawed for several reasons:

- The UN-led federation of 1952 and Ethiopia's subsequent illegal annexation of Eritrea in 1962 cannot be used to override the fundamental principle of uti possidetis (colonial boundaries). The colonial borders of Italian Eritrea were clearly defined and internationally recognized.

- Ethiopia's annexation of Eritrea in 1962 was an illegal act that violated the UN-mandated federation. This illegal occupation cannot be used as a basis for territorial claims after Eritrea achieved independence through its liberation struggle.

- The Organization of African Unity (OAU, now AU) Cairo Declaration of 1964 specifically endorsed the principle of respecting colonial borders to prevent territorial disputes. This principle has been consistently upheld in African territorial disputes and international law.

- Eritrea's independence in 1991 (formally recognized in 1993) was achieved through a liberation struggle and subsequent referendum, establishing its sovereignty within its colonial borders. Any suggestion that Ethiopia could have claimed Eritrean territory through legal channels contradicts both international law and the principle of self-determination.

- The UN's involvement in the 1940s was superseded by subsequent events, particularly the illegal annexation and the 30-year liberation struggle. It cannot be retroactively used to justify territorial claims against a sovereign nation that achieved independence through armed struggle and popular referendum.

This type of insinuation undermines both the legitimacy of Eritrea's independence struggle and established principles of international law regarding territorial sovereignty and self-determination.

Shaleka Dawit: “Another opportunity for Ethiopia to claim the Assab port was during the Badme War in 1999 over the boundary between Ethiopia and Eritrea. At one point, Ethiopian troops overwhelmed the Eritrean troops who withdrew from Assab. I am quite sure Meles knew that Assab was there for the taking: (Later confirmed by former Eritrean officials in the book by Dan Cornell: Conversations with Eritrean Political Prisoners) without more fighting, but he did nothing. Had he moved in and occupied the port he could have bargained to keep Assab in exchange for Badme, but Meles did not want to. That was the last ‘missed’ opportunity. Eritrea will continue to have complete sovereignty over every inch of its territory. At this point, one way that the argument over access to the sea can be addressed is through the Convention on Transit Trade of Land-locked States, which says that landlocked countries must be granted free transit through neighboring states and free access to the sea.”

AB: The statement contains multiple significant falsehoods about the Badme War and its resolution:

- Ethiopian forces never reached or controlled Assab during the 1998-2000 conflict. The claim that "Ethiopian troops overwhelmed the Eritrean troops who withdrew from Assab" is entirely false.

- The citation of "Conversations with Eritrean Political Prisoners" to support claims about Assab being "there for the taking" is questionable, given the context and nature of such testimonies.

- The suggestion that Assab could have been "bargained" for Badme fundamentally misunderstands both:

- The legal principles governing territorial sovereignty

- The binding nature of colonial boundaries in African territorial disputes

- The absolute illegality of acquiring territory through force

- Characterizing these events as "missed opportunities" to take Eritrean territory is particularly problematic as it suggests that military conquest would have been a legitimate means of acquiring territory, which directly contradicts international law.

This passage's only accurate conclusion is that "Eritrea will continue to have complete sovereignty over every inch of its territory." This aligns with international law and the principles of territorial integrity established in the OAU/AU framework.

The reference to the Convention on Transit Trade of Land-locked States is appropriate, as this represents the legitimate legal framework for addressing access to the sea rather than territorial claims or military action.

Shaleka Dawit: “The rights and claims of Ethiopia based on geographical, historical, ethnic or economic reasons, including in particular Ethiopia’s legitimate need for adequate access to the sea.” Explicitly stated: “the rights and claims of Ethiopia” not Eritrea: **those rights and claims still exist. Why would it not be possible to claim it now, even though Eritrea is independent? A good argument could be made. As I mentioned in the introduction of this series, a good relationship with Eritrea based on mutual economic, security, and historical and cultural interests could make it easier for Ethiopia to acquire Assab because Eritrea does not even need it. It is strategically located to serve Ethiopia’s interests.”

AB: This statement is deeply problematic and potentially dangerous for several critical reasons:

- The assertion that "rights and claims" from the 1940s could override Eritrea's sovereignty is a fundamental violation of:

- International law

- The UN Charter

- The African Union's foundational principles

- The principle of self-determination

- The suggestion that Ethiopia could "acquire Assab because Eritrea does not even need it" is both:

- A violation of territorial sovereignty

- A dangerous precedent suggesting stronger nations can claim territory from neighbors based on their "needs."

- Using outdated colonial-era documents to justify modern territorial claims against a sovereign nation that:

- Fought a 30-year liberation struggle

- Achieved independence through referendum

- Has internationally recognized borders is legally and ethically untenable.

- The phrase "make it easier for Ethiopia to acquire Assab" implies potential coercion or pressure against a sovereign nation, which could be interpreted as advocating for territorial aggression.

- This type of reasoning, if accepted, would destabilize the entire international order by suggesting that:

- Historical claims can override current sovereignty

- Economic needs justify territorial acquisition

- Stronger nations can claim territory from weaker neighbors

These arguments disregard international law and could be seen as promoting conflict between nations. The only legitimate approach to port access is through standard international agreements and protocols regarding landlocked nations, not through territorial claims.

Conclusion

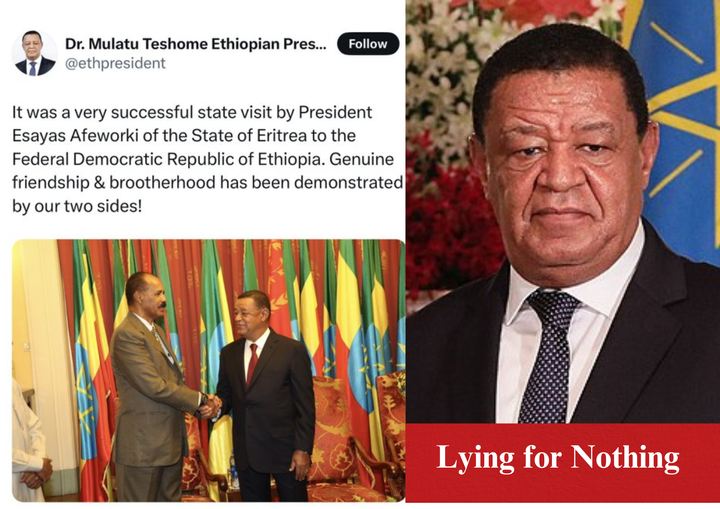

It is deeply troubling that Shaleka Dawit, a 90-year-old former official who served under multiple Ethiopian regimes (Haile Selassie, the Derg, and later went into exile during the TPLF period), would promote such dangerous historical revisionism. His statements not only misrepresent well-documented historical facts about Eritrea's independence struggle and sovereignty but also advocate for territorial aggression based on distorted interpretations of 1940s-era documents.

As someone who witnessed these historical events firsthand and served in positions of authority, his attempt to rewrite history to justify territorial claims against Eritrea is particularly irresponsible. Such statements could mislead younger generations and potentially incite regional tensions. For a public figure of his age and experience to promote narratives that could lead to conflict rather than advocating for peaceful cooperation and respect for international law represents a concerning departure from the elder statesman's traditional role of promoting wisdom and peace.

The suggestion that Ethiopia could or should acquire Eritrean territory, particularly the port of Assab, through various means is not just historically inaccurate - it's dangerous warmongering that disregards:

- The sacrifices made during Eritrea's 30-year liberation struggle

- Eritrea's internationally recognized sovereignty

- Established principles of international law

- The potential human cost of regional conflict

This type of narrative does a disservice to both Ethiopian and Eritrean youth, who deserve to inherit a future based on mutual respect, cooperation, and peaceful coexistence rather than territorial disputes and potential conflict.

Comments ()