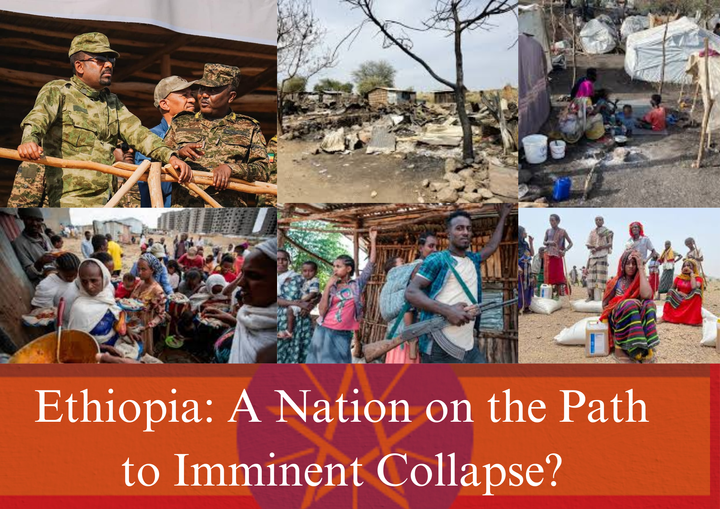

U.S. Faces Shifting Alliances in the Horn of Africa as Eritrea, Somalia, and Egypt Form Strategic Bloc

The Economist’s latest article revisits discredited claims about Eritrean troops in Tigray, overlooking the Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission’s ruling on sovereignty. This narrative distorts Eritrea’s role and undermines regional cooperation efforts with Somalia and Egypt.

Amanuel Biedemariam 10/31/2024

The Economist has once again published a misleading account of events in the Horn of Africa, as seen in its latest article on October 27. This time, the magazine rehashes unsubstantiated claims about Eritrean troop presence in Tigray, relying on dubious sources to perpetuate allegations that have long been discredited. These claims are, in reality, a thinly veiled reference to Eritrean territories that were unequivocally recognized as sovereign under the final and binding decision of the Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission (EEBC).

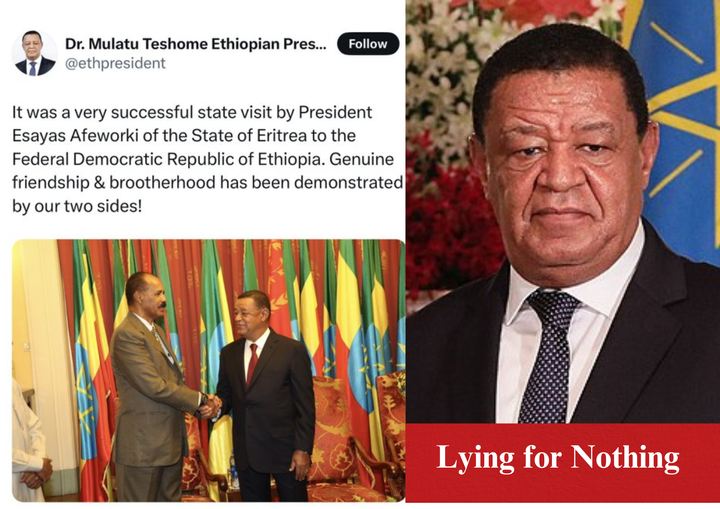

Moreover, The Economist distorts history to undermine Eritrea’s legitimate liberation struggle and misrepresents the 2018 rapprochement between Eritrea and Ethiopia, which was based on mutual respect for the EEBC Award, as well as each nation’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. Its portrayal of the conflict in Tigray is similarly inaccurate, failing to capture the complexity of the causes and dynamics at play.

These distortions go beyond the typical careless and condescending coverage of the Horn. A series of recent developments raise questions about the underlying motives: increased activity from Whitehall, intensified negative campaigns led by the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) and figures such as Lord Alton, and discussions on the "security of the Red Sea" by the MI6 Deputy Director during a recent visit to the region. These activities hint at a broader agenda that warrants scrutiny.

In its latest piece, The Hill asserts:

"The recent summit between Egypt, Eritrea, and Somalia marks a major shift in the geopolitics of the Horn of Africa—a region plagued by chronic instability, rivalries, and competing interests. This trilateral meeting, held in Asmara, Eritrea, was ostensibly aimed at presenting a united front amid regional security challenges. The 'elephant in the room,' however, was Ethiopia—Africa's second most populous nation and a key player in regional trends.

While the summit positioned itself as aligned with each country's strategic interests to maintain regional stability, its underlying goal appeared to encircle neighboring Ethiopia, where tensions over its influence continue to simmer. Officially, discussions focused on a pact to enhance cooperation and regional autonomy. Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, and Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud emphasized territorial integrity and resistance to external interference in their joint statement."

This narrative attempts to frame positive regional cooperation as a conflict-driven development. Such framing is a familiar pattern, especially as the U.S. views any regional alignment outside established bodies like IGAD as a potential threat to its interests. Since taking office, the Biden administration has been wary of alliances that bypass U.S.-backed structures and has actively sought to counteract the growing ties between Eritrea and Ethiopia. Notably, the Eritrea-Ethiopia peace agreement and the Tripartite Agreement with Somalia were both achieved during the Trump administration—a fact that adds a layer of complexity to current U.S. relations in the region. Ethiopian Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Ambassador Dina Mufti highlighted this tension, pointing out that "third-world countries like Ethiopia are not allowed to make decisions and chart their path," a statement which he illustrated by noting U.S. disapproval of Ethiopia’s alignment with Eritrea.

The strengthening of ties between Eritrea, Somalia, and Egypt has implications for U.S. influence, especially given the strategic positioning of these countries along key maritime routes in the Red Sea, Bab al-Mandeb, and the Indian Ocean. This alliance could reduce U.S. control over these waterways, where it has historically maintained influence through partnerships with nations like Ethiopia, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and others since 1948. If this alliance expands to include regional actors like Sudan, Djibouti, Yemen, and Saudi Arabia, it could foster a security arrangement independent of U.S. influence, drawing interest from other powers such as China and the Gulf States. In this increasingly multipolar landscape, where rising powers like China, Russia, and India assert more influence in Africa, the U.S. risks being isolated from one of the most critical and resource-rich regions if such an alliance gains traction.

Conclusion:

A pragmatic approach for the U.S. would be to seek partnerships with Eritrea, Somalia, and Egypt, recognizing that these nations increasingly have the leverage, resources, and support from other global powers to shape their destinies. These countries occupy geostrategic positions along vital maritime routes and possess resources valuable to various international interests. As other powers, including China, Russia, and Gulf nations, continue to strengthen ties with them, it becomes clear that attempts to exert control are less effective than fostering respectful, cooperative partnerships based on mutual interests.

By engaging these nations constructively, the U.S. could build trust and find common ground in maritime security, counterterrorism, and regional stability. Rather than viewing their alliances as threats, the U.S. could benefit from aligning with them on shared goals, such as economic development, counter-piracy, and addressing regional conflicts. Adapting its strategy would allow the U.S. to remain a relevant and respected partner while acknowledging the changing multipolar landscape in the Horn of Africa and Red Sea regions.

Aman@nefasit.com

Comments ()